After just three months, Donald Trump’s presidency certainly looks like a disaster for climate policy. Trump has filled his administration with climate deniers, plans to disembowel the Environmental Protection Agency, and signed a big executive order to tear up President Obama’s regulations on greenhouse gases.

It all seems staggeringly consequential.

Lately, however, some liberals and environmentalists have taken a surprisingly sanguine view of these moves, arguing that Trump probably can’t do too much climate damage. Obama’s policies aren’t easy to unwind, after all. Coal is declining no matter what Trump does. Wind and solar are growing regardless. China and India still plan to pursue a greener future, as do many states and cities. Michael Bloomberg and Carl Pope wrote a widely read New York Times op-ed making this case, titled: “Climate Progress, With or Without Trump.”

So, uh, who’s right, the pessimists or the optimists? Is the Earth screwed, or do Trump’s policies just not matter that much in the grand scheme of things?

While there are good points on both sides, I tend to think the This Is Very Bad view is closer to the mark here. What the optimistic view misses is that we were making woefully insufficient progress on climate change even before Trump. Yes, coal is declining and renewables are booming in the electricity sector. But that’s only a tiny slice of the climate problem. If we really want to stop global warming, we’d need sweeping changes to virtually every sector of the economy — and fast. Even under Obama, we weren’t close to doing that. The US wasn’t even on pace to meet its (weak) Paris climate targets. They look extra-impossible now.

That’s why Trump matters. States and cities can’t do this alone. Stronger federal climate policies would likely be crucial for any “deep decarbonization” push, but Trump isn’t planning stronger policies; he wants to chip away at what little already exists. That’s a big deal, especially with so little time left to avoid 2°C of warming.

Now, this doesn’t mean the Earth is doomed, or that there are no options for further decarbonization in the years to come. But the first step in thinking about the road ahead for climate policy under Trump is understanding why federal action was so significant — and then figuring out what’s still possible as Trump rolls it back.

Even before Trump, the US wasn’t on pace for “deep decarbonization”

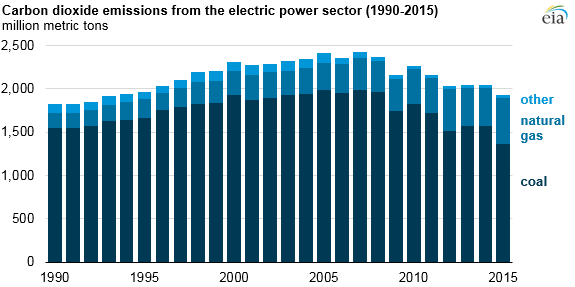

The case for climate optimism makes more sense if you mainly focus on trends in the US electricity sector. Last year, America’s power plants emitted 27 percent less carbon dioxide than they did in 2005. To put that in perspective, Obama’s Clean Power Plan was estimated to cut power plant emissions 32 percent by 2030. We’re nearly there already:

So you can see where the “Trump doesn’t matter” argument originates. Emissions are mainly dropping because hundreds of coal plants have been pushed into retirement, thanks to cheap natural gas from fracking and the stunning growth of wind and solar power — which have been bolstered by state renewable standards, federal tax credits, and steep cost reductions.

Trump can’t undo all of these trends even if he scraps the Clean Power Plan. He has no desire to halt the fracking boom, and Congress is unlikely to repeal those popular renewable tax credits. And most state renewable policies will remain in place, which means wind and solar will keep chugging along.

But this drop in electricity emissions comes with two massive caveats:

1) Current electricity trends aren’t nearly sufficient for deep decarbonization. If the US wants to do its part to halt global warming, it’s not enough for electricity emissions to dip moderately. They have to go to zero — within a couple of decades. That’s a mind-bogglingly difficult task, and we’re not really on track to do it.

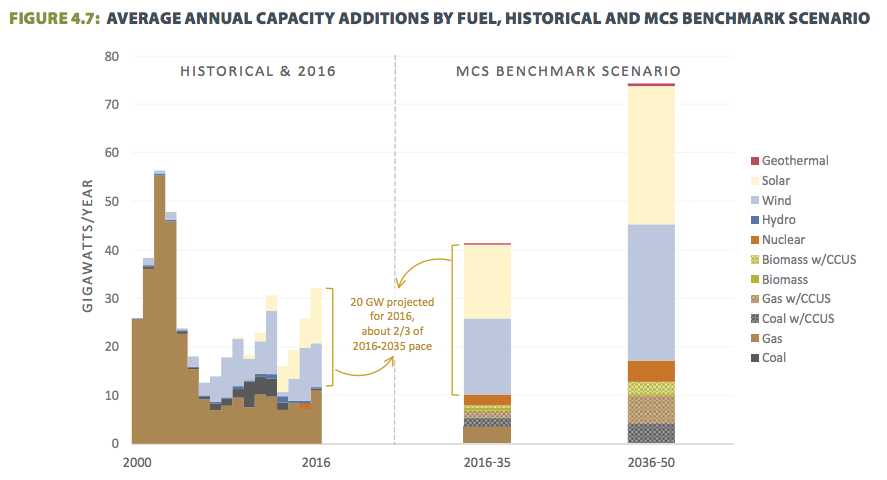

Late last year, the Obama White House put out a big report on what it called “deep decarbonization” sketching out four different scenarios for a near-zero-CO2 power sector in 2050. The chart below shows what sorts of electric capacity we’d need to be adding between now and then to meet one such decarbonization scenario:

As the graph on the left shows, the US has mainly been adding natural gas (in brown), wind (in blue), and solar (in yellow) capacity in recent years. That’s the lauded clean energy transition we’re now seeing.

But it won’t suffice for deep decarbonization. As the graphs on the right show, annual natural gas additions would need to decline, not continue apace. Wind and solar would need to ramp up dramatically — not just maintain their course. On top of that, we’d likely need to add significant nuclear capacity as well as carbon capture for coal, gas, and biomass every single year through 2050. Right now we’re barely building any.

Only a handful of states are even beginning to grapple with this reality. Yes, California and New York both aim to get 50 percent of their electricity from renewables by 2030, (though neither has plans to expand nuclear or carbon capture, and California wants to shut down its last nuclear plant by 2025). But those two blue states, while important, account for less than 10 percent of the nation’s emissions.

Meanwhile, other large states, like Texas or Florida or Ohio, aren’t making any plans at all for similarly drastic reductions in electricity emissions. A large chunk of states in the South don’t even have clean-energy standards. That’s why federal action was such a big deal. Obama’s Clean Power Plan set weak targets initially, but it was conceivably something to build on through 2050, nudging states such as Georgia and Louisiana toward the sort of decarbonization pathways that, say, New York is contemplating. Now Trump plans to scale back that policy, leaving states to fumble (or not) on their own.

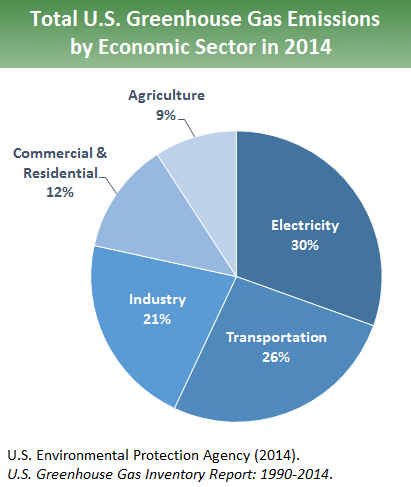

2) Electricity is only part of the decarbonization challenge anyway. What’s more, even if trends in the power sector look promising, electricity is only responsible for about 30 percent of US greenhouse gas emissions. The rest comes from a vast array of different sectors, including cars and trucks, industries like steel and cement, refineries, natural gas use for heating in buildings, methane from agriculture and landfills, and so on:

In most of these other sectors, the United States has made remarkably little headway. Emissions from transportation have been rising since 2012, with electric vehicles still just 0.7 percent of the total fleet. Agriculture emissions haven’t budged for decades. Emissions from buildings and industry have been ticking upward of late.

To meet US climate goals, overall greenhouse gas emissions need to fall 80 percent or more by 2050. But apart from California, which is developing a comprehensive plan to tackle non-electric sectors, few states are really thinking about transportation or industry or agriculture. For the most part, that’s been the purview of the federal government, which under Obama has set stricter emissions standards for cars, trucks, household appliances, landfills, methane leaks from oil and gas, and so on. Now Trump plans to undo many of those rules.

So that’s the climate landscape in the United States: decent progress on electricity emissions coupled with scant progress in most other sectors. Even if states and cities keep doing what they’ve already been doing under Trump, that won’t be nearly enough to slow global warming. Not even close.

Why federal policy was vital for decarbonization

President Obama’s climate policy, for all its shortcomings, was an attempt to speed up the sluggish progress on emissions described above, using any and all executive branch tools he could find. The Clean Power Plan would prod a greater number of states to focus on decarbonizing. And other EPA regulations would tackle the neglected non-electric sectors. Trump plans to scuttle that, and those features won’t be easy to replace.

Another key aspect of Obama’s climate strategy was ramping up R&D for new energy tech that could help us achieve deeper emissions cuts down the road. That included research for advanced solar, wind, and battery technology; loan guarantees for a carbon capture project in Texas and companies such as Tesla; research into long-shot tech like advanced biofuels under ARPA-E; support for grid modernization; and more.

These early-stage projects take time to show results, if they ever do. Federal investments in hydraulic fracturing technology began in the 1970s and didn’t pay off until the mid-2000s. But the hope was that today’s R&D would eventually provide vital new tools for the wrenching energy shifts we need in the 2030s and beyond. Under Trump’s budget proposal, many of those R&D programs are now endangered.

Then there’s the international stage. Stopping global warming obviously requires every nation to take action, not just the US. And here, the Obama administration has played a more proactive role than is often acknowledged. As David Victor, a political scientist at the University of California San Diego, told me, US bilateral talks with China were vital for framing the Paris climate deal and helping to get China comfortable with the accord. A breakthrough in talks between the US and India also helped pave the way for a landmark deal under the Montreal Protocol to phase out hydrofluorocarbons.

Trump is now planning either to withdraw from Paris altogether or at least scale back US commitments under the deal. While that won’t blow up the treaty, and other countries will still pursue their own policies, the loss of the US involvement will be keenly felt. The Obama administration, for instance, was a key advocate for a more robust review of individual country climate pledges. “That was a place where US leadership was important,” Victor says.

“I’m not concerned that Trump will kill the Paris climate deal,” he adds, “but I am concerned that a lot of the practical momentum and important detailed procedural work could be severely harmed.”

To be clear, US climate policy was much too weak under Obama and likely would have been much too weak under Clinton (particularly so long as Congress refused to pass climate legislation). But both politicians at least envisioned a path toward lower emissions, pushing in the general direction of decarbonization. It’s no small thing that the US now has a president who wants to abandon or disable many of those tools.

So is there any hope for climate policy under Trump?

I mentioned in the beginning that Trump’s moves don’t have to be the end of the world for climate policy, and I (mostly) do believe that. But a key starting point is to think seriously about what deep decarbonization entails — and not get too complacent about the encouraging electric sector trends of the past eight years.

How to move forward on climate policy under Trump is obviously a huge topic, larger than any one piece can tackle. But based on the above, here are a few ideas:

1) States need to think harder about decarbonization outside of electricity. The greening of the utility sector via renewables and natural gas is promising, but there’s a lot more to do. California passed a law last year, SB32, that will begin aggressively tackling emissions from sectors like industry, agriculture, and buildings. Other states concerned about climate change could follow suit. (New York’s recent efforts on electric vehicles are another possible model.) The same goes for cities, which can have a large impact on emissions through urban planning and infrastructure.

2) Preserving EPA authority over greenhouse gases for future presidents. The Trump administration is likely to start dismantling Obama’s federal climate policies, from the Clean Power Plan to methane rules, and that will be difficult to stop. Yet the EPA will still have legal authority over greenhouse gases — unless Congress amends the Clean Air Act to take this away. So long as that authority remains intact, future presidents could conceivably redouble efforts to cut emissions through federal initiatives. Just 41 senators could filibuster any attempts to amend this policy.

3) Protecting energy R&D programs. As the White House deep decarbonization report notes, driving sharp reductions in emissions past 2030 will almost certainly require new tools and technologies that are still unproven, from batteries to carbon capture. Various R&D programs, particularly out of the Department of Energy, are likely to play a key role in bringing some of this tech forward. Trump has signaled that he would like to slash these R&D programs, whereas various Democrats and Republicans in Congress would like to protect them. How this battle shakes out could be hugely significant to future climate policy. (Private sector funding for energy R&D, à la Bill Gates’s new initiative, could also prove worthwhile.)

4) Democrats and Republicans could find common ground on energy programs that could pay off later. The current Republican Party is overwhelmingly hostile toward efforts to fight global warming. Most don’t even think it’s real. But there are nuances. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) has been working with key Republican senators like Lamar Alexander (R-TN) and even Jim Inhofe (R-OK) on policies to facilitate the development of a new generation of (hopefully) safer, cheaper, low-carbon nuclear reactors. Similarly, at least some Republicans seem interested in carbon capture technology. This stuff seems small-bore, but it could reap benefits down the road.

This list barely scratches the surface of how climate policy can survive or evolve under Trump. Environmental activists will likely continue fighting for coal plant closures or blocking fossil fuel infrastructure. Plus, there’s always the prospect of unforeseen policy surprises over the next four years: Some of the most important climate tools of the Obama era, such as EPA authority over greenhouse gases and CAFE standards, were put in place during the Bush era. Perhaps the Trump era has similar plot twists in store.

Finally, there’s the big picture to consider. A Trump administration may be able to delay US and global climate action long enough to put the world on pace to blow past the much-feared 2°C global warming threshold. Our margin for error for avoiding 2°C was already razor-thin.

But even if that happens, there’s still ample reason to try to decarbonize to avoid 2.2°C or 2.5°C or 3°C or whatever level is attainable. That’s still one of the biggest long-term policy challenges of the 21st century — and will be long after Trump is gone.

Further reading:

- Here’s a handy database of different state energy policies, which are going to become increasingly important in the Trump era.

- Here’s our previous coverage of California’s aggressive plan for deep decarbonization. Note, however, that the state plans to close Diablo Canyon, its last large nuclear power plant, which could end up being a major setback for reducing emissions. New York and Illinois, by contrast, are striking more of a balance by promoting renewables but also saving their endangered zero-carbon nuclear plants.

- The White House report on deep decarbonization is really worth reading, not least to give a sense of the scale of the challenge. Or, for a more global perspective, check out this “roadmap” of what’s required to meet the Paris climate goals. It’s far more radical than is commonly appreciated. (Think: no new combustion engine vehicles sold after 2030.)